Supervisor Spotlight: Dr Simon Tang

Sustainable drug discovery inspired by nature’s own chemistry

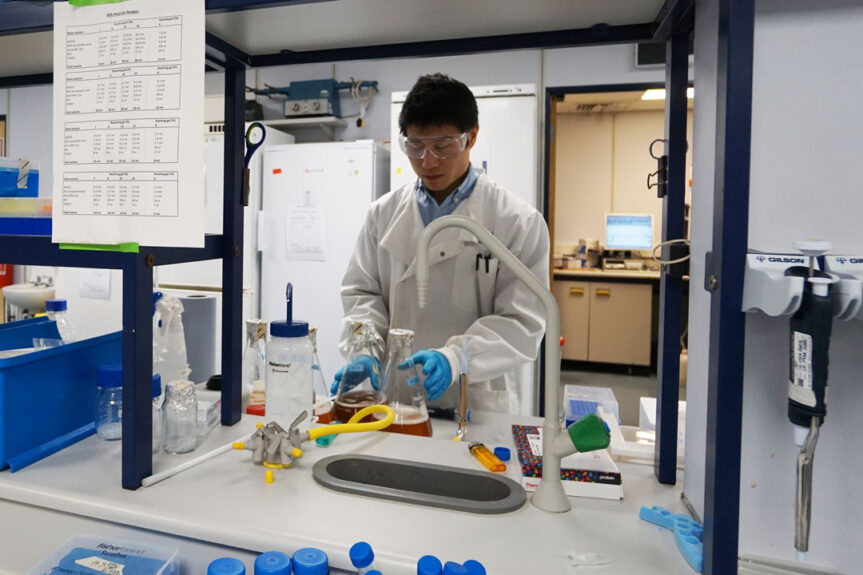

Dr Simon Tang started as a Research Fellow in the Department of Life Sciences at the University of Bath in 2025. As an early career researcher, his work brings an exciting, sustainability-driven angle to healthcare innovation, using enzymes as greener tools to develop next-generation medicines.

At the heart of his work is a key question:

Why peptides matter and why “cyclic” changes everything

Many modern medicines are built from small molecules — familiar examples include drugs like aspirin or paracetamol. But in biomedical research, some of the most important disease targets are still considered extremely difficult to treat.

That’s because many diseases (including cancer and autoimmune conditions) are driven by protein–protein interactions, where large proteins interact across broad, relatively flat surfaces. Traditional small-molecule drugs often struggle to effectively disrupt these interactions.

On the other hand, antibody-based medicines can be highly effective — but because they are so large, they typically cannot enter cells, which limits what they can target.

This is where cyclic peptides come in.

Cyclic peptides are small chains of amino acids (like “mini-proteins”), but with one crucial difference: instead of being linear, they’re stitched into a loop. That change in shape can help them resist breakdown in the body, meaning they can persist longer and reach the biological target where they’re needed.

In practice, this enables cyclic peptides to bind across flatter protein surfaces, offering a promising route to disrupt interactions that were previously hard to target.

Simon describes cyclic peptides as occupying a “Goldilocks zone” between small molecules and antibodies — potentially opening access to disease targets that are currently considered “undruggable”.

The sustainability challenge hidden inside drug discovery

While cyclic peptides are promising as medicines, they are notoriously difficult to manufacture.

Many current peptide synthesis methods rely on highly toxic organic solvents, including dichloromethane (DCM) and dimethylformamide (DMF). These can be manageable at small laboratory scales, but become far more problematic when scaling production towards real-world drug development.

As Simon explains, if a peptide-based therapeutic is ever needed at kilogram scale for global distribution, it is not feasible — or safe — to produce it using large volumes of hazardous solvents.

This challenge connects directly to the CSCT’s mission: sustainability must be designed into future technologies from the beginning, rather than treated as a downstream issue.

Using enzymes as a clean alternative

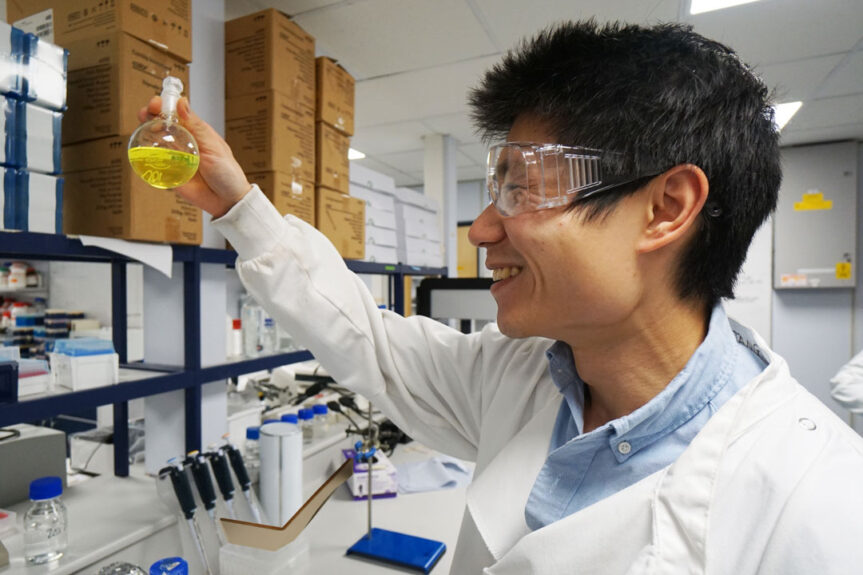

Simon’s solution comes from a powerful philosophy: don’t fight nature — learn from it.

My research philosophy has always been take inspiration from nature.

Many plants already produce cyclic peptides naturally as part of their defence systems against pests. These plants contain enzymatic “machinery” capable of forming peptide cycles efficiently and safely, in water-based systems.

Simon’s research focuses on leveraging this natural process through biocatalysis, using enzymes to drive chemical transformations that would otherwise require harsh reagents and conditions.

In the context of sustainable technologies, enzyme-driven synthesis has major advantages:

- Water-based reaction systems instead of toxic solvents

- Lower hazardous waste burden

- Reduced reliance on precious metal catalysts

- Potential for scalable, greener manufacturing routes

Simon is also working on improving the accessibility of biocatalysts — addressing the challenge that enzymes are often harder to “pick up and use” than conventional chemistry reagents, because stability and availability can be limiting factors for end users.

A breakthrough direction: screening millions of peptides inside bacteria

Beyond sustainable synthesis, Simon is also targeting a major bottleneck in healthcare innovation: the early-stage drug discovery process.

Drug discovery traditionally requires testing huge numbers of candidate molecules to find just one that truly works — a process that is slow, expensive, and resource-intensive.

In a single flask, you can potentially screen millions of peptide variants — which makes discovery much faster and more scalable.

Simon describes an exciting screening strategy that uses engineered bacteria to generate vast libraries of peptides — potentially up to 10 million variants in a single flask — without relying on solvent-heavy chemistry.

This approach links performance to survival through a selection process: bacteria that produce better peptides grow more effectively, allowing researchers to “enrich” the best candidates and rapidly identify them using DNA sequencing.

It’s an example of how nature-inspired systems can help create leaner, faster, and more sustainable pipelines for therapeutic discovery.

Connecting to CSCT: circular thinking in life sciences

Sustainability is often discussed in terms of materials, plastics, energy systems, or industrial processes — but Simon’s work reminds us that sustainability challenges exist in healthcare too.

From his perspective, life sciences can contribute a crucial mindset: biology is inherently circular.

Biological systems are defined by feedback loops, recycling mechanisms, and regeneration — from molecular building blocks, to proteins, to whole cells. Simon sees strong parallels between this and the goals of circular manufacturing and sustainable technology development.

And he also highlights something central to the CSCT identity: interdisciplinary research is essential not only for scientific breakthroughs, but also for enabling real-world translation.

Why the CDT environment matters

Simon emphasises that collaboration across disciplines is not a “nice-to-have” — it actively shapes how research moves into the world.

In his own work, bridging chemistry and biology helps break down silos and opens up new ways of asking research questions. He also sees the CSCT’s cohort structure as a powerful mechanism for spreading ideas across the University, as researchers and students carry methods, tools, and insights between departments.

Crucially, he notes that sustainability being a central pillar of the CSCT provides a grounding reference point — helping researchers stay anchored to why their work matters, even when experiments become highly specialised.

Looking forward: building truly circular technologies

For Simon, the long-term vision is clear: future technologies — including healthcare innovation — should be designed to support circularity.

He is excited by the possibility of systems where products can be created, used, and then degraded or recycled back into starting materials in a meaningful loop.

It’s a sustainability principle that fits perfectly within the CSCT mission: combining deep technical research with the design of safer and more circular pathways — from lab innovation to real-world impact.

Advice for future CSCT applicants

Simon’s message to prospective researchers is simple and honest: the CSCT is ideal for students who are ready to embrace breadth.

A PhD within our CDT is best suited for someone who wants to work across boundaries, stay open-minded, and explore research areas beyond their original discipline — all while staying anchored to sustainability as the “guiding light.”

And beyond the research environment, Simon adds another reason Bath is a great place to build a future:

Bath is a really supportive environment — it’s a campus university, it’s collaborative, and it’s just a great place to live.